About 400 million years ago, our ancestors had an aquatic lifestyle with a fish-like body form. Ancestral vertebrates adapted to a terrestrial life by gradually transforming gills and fins into the throat and limbs, enabling them to conquer the land. When comparing the cartilages comprising the pharyngeal skeleton in fish gills with those in our throat, the morphology is very different. However, since both skeletons are thought to have a common developmental origin, neural crest cells, in the embryonic pharynx, scientists have assumed that this transition involved gradual changes of form and shape during evolution.

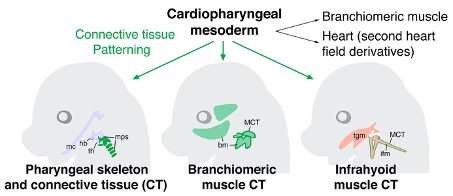

In our study we used genetic lineage tracing to investigate the cellular origin of the throat in the mouse model. We found that cardiopharyngeal mesoderm (CPM), known to give rise to head and heart muscle, makes a major contribution to mammalian pharyngeal structures. Despite the different positions of the heart and throat in the adult, these structures thus arise from a common population of progenitor cells during early development. Indeed, pharyngeal cartilages, muscles and connective tissues in the throat derive from CPM, which makes a strikingly complementary contribution to the pharynx to that of neural crest derived mesenchyme. This suggests that our throat evolved by new mesodermal contributions from CPM rather than exclusively by gradual remodelling of neural crest-derived gills in fish-like ancestors.

In addition to providing new insights into the development and evolution of the pharynx, our results have implications for understanding the origins of human congenital defects. Connective tissue surrounds forming organs and is important for normal developmental patterning. For example, neural crest cell derived connective tissue plays an important role in the patterning of head muscles, ensuring their correct attachment sites, as well as in the evolution of craniofacial muscle diversity during vertebrate radiation. We used mouse genetics to investigate whether CPM-derived connective tissue also has such a patterning role. We found that mice lacking one copy of the CPM regulatory gene Tbx1, encoding a T-box containing transcription factor, have neck muscle patterning defects, suggesting that CPM derived connective tissue is required for the proper formation of muscles in the throat. This previously unappreciated role of CPM provides new clinical insights into the etiology of pharyngeal defects found in certain diseases, such as those observed in 22q11.2 deletion (or DiGeorge) syndrome patients, where dysphagia and neck muscle hypotonia are associated with haploinsufficiency for TBX1. Moreover, CPM derived connective tissue may have played a role in the evolution of diverse neck muscles during tetrapod evolution.

To know more :

Development. 2020 Feb 3;147(3). pii: dev185256. doi: 10.1242/dev.185256.

Noritaka Adachi 1, Marchesa Bilio 2, Antonio Baldini 2 3, Robert G Kelly 1

1Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS UMR 7288, IBDM, 13009 Marseille, France adaraptor@gmail.com Robert.Kelly@univ-amu.fr.

2CNR Institute of Genetics and Biophysics Adriano Buzzati-Traverso, Via Pietro Castellino 111, 80131 Naples, Italy.

3Department of Molecular Medicine and Medical Biotechnology, University of Naples Federico II, Naples 80131, Italy.

-

Contact

Noritaka Adachi – adaraptor@gmail.com

Robert Kelly – robert.kelly@univ-amu.fr